20th anniversary of human presence on ISS, New Kepler telescope data, smallest rogue exoplanet and a new way to ‘see’ dark matter

ISS celebrates 20th year of continuous human presence

On the 2th of November 2020, the International Space Station (ISS) celebrated its 20th year of continuous human occupation. The day was celebrated as a great victory for international cooperation, being heralded not only as the proof that humanity can live in space but also that they can cooperate in a meaningful way.

Image Credit: NASA

Image Credit: NASA

The station started its life in the 1980’s under Ragan in the height of the cold war where it had some level of success but this changed after the Challenger disaster in 1986. It was not until several years later in 1990, when Clinton invited Russia to join in on a collaboration, the birth of the coalition surrounding the station. Today over 100 countries have participated in the ISS with 241 visitors from 19 countries performing over 3000 experiments in 0G.

The future for the ISS is still quite bright, with there being budget to keep it going for at least another 10 years. We will have to wait and see what happens afterwards, especially with commercial space travel growing at the rate that it is.

Astronomers discover smallest rouge exoplanet to date

Heavy objects bend light similarly to how a telescope does it, the more massive the object the stronger this effect is. Just like with a telescope, we can observe objects very far away by using these gravitational lenses. However, unlike with a telescope we cannot point or move it, and we are forced to look at whatever this gravitational telescope is pointed at, making them more of an opportunistic instrument. Still, from time to time an interesting object moves into such a gravitational telescope, giving us a glimpse of objects that we would otherwise never be able to resolve.

The planet was detected by a Polish team from the University of Warsaw and is thought to be the smallest object detected outside of our solar system. The planet, called OGLE-2016-BLG-1928 is estimated to be about the size of Mars. The planet is a so-called rouge planet, because it does not have a host star and travels through space on its own.

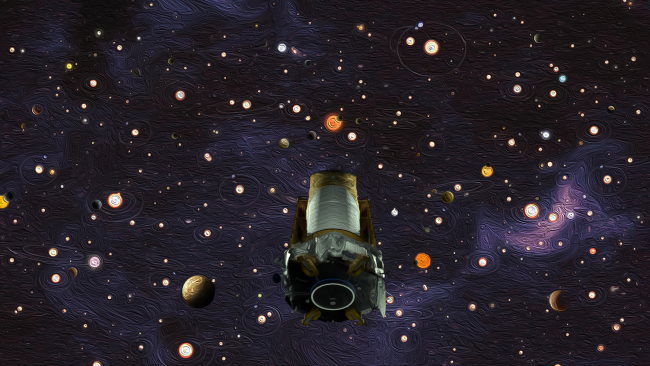

New analysis of Kepler data suggests that Earth-like planets are not as rare as we thought

The Kepler space telescope by NASA observed half a million stars over the course of 9 years, very accurately measuring their brightness in order to find any planets that eclipse the star. Over 2,600 planets were found in this way and scientists keep finding new ones in the data, despite the fact that the telescope ceased operation two years ago.

Image Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/W. Stenzel/D. Rutter

Image Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/W. Stenzel/D. Rutter

Several projects are being done with the data, including a citizen science program. Now a large collaboration between NASA, SETI and other scientists was formed to perform a statistical analysis of the entire nine year dataset combined with other observations. From this, they have concluded that roughly half of the Sun-like stars in our galaxy could have an Earth-like planet around them, that’s about 300 million in total!

Unfortunately this analysis merely extrapolates the current findings and fills in the gaps based on other data. We do not actually know where these planets are, just that they are probably all over.

Observing a rocky planet close to a star is very difficult overall, as their effects on the star are minimal and they usually get lost in the halo of the star. You can compare it to trying to photograph a firefly next to a lighthouse at 4 kilometers distance. However, with the newest generation of telescopes, we hope that progress can be made in this direction.

Astronomers find a new way to ‘see’ dark matter

Dark matter is a mysterious substance that does not interact with light in any way, but somehow still has weight. We know that it exists, because if we look at a galaxy and sum up all the matter inside of it (e.g. stars, dust, etc.) we find a mass that is much lower than what one would expect when looking at the rotation of the same galaxy. This discrepancy is what we call dark matter. In fact around 85% of the universe is estimated to be dark matter.

What dark matter is exactly remains a mystery even today, but recently an advancement has been made by PhD student Pol Gurri from the Swinburne University of Technology. The student used gravitational lensing to measure dark matter in lensed galaxies, comparing the expected rotations to the distorted observations. By reverse engineering the ‘lens’, it was possible to accurately calculate how much invisible matter is between the observer and the target. This method is roughly 10 times more precise than current methods.

In Gurri’s own words: “It’s like looking at a flag to try to know how much wind there is. You cannot see the wind, but the flag’s motion tells you how strongly the wind is blowing.”